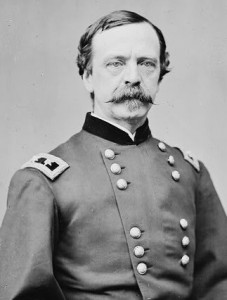

Library of Congress

On February 27, 1859, U.S. Congressman Daniel E. Sickles (D- NY) approached the Washington D.C. district attorney, P. Barton Key, in Lafayette Square and shot him three times. Then, walking to the house of Attorney General Jeremiah Black, Sickles confessed to the shooting and surrendered his gun. Word came later that Key, the son of “Star-Spangled Banner” author Francis Scott Key, had died of his wounds.

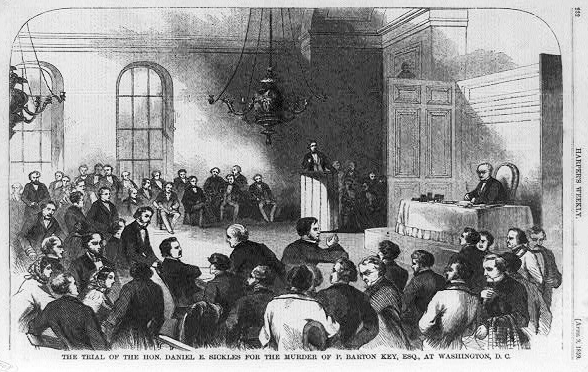

Although a Congressman shooting a prominent district attorney in cold blood on a city sidewalk is historic in its own right, it was the ensuing trial of Dan Sickles that would produce a first in American legal history.

The story began when Sickles discovered that his young wife, Teresa Bagioli, was having an affair with Barton Key. She had confessed to the indiscretion on the evening of February 26, and the following day, Sickles observed Key walking past his house waving a white handkerchief in the direction of Teresa’s bedroom window. Becoming enraged, Sickles grabbed a pistol and ran out of the house. He caught up with Key in Lafayette Square near an establishment called the Clubhouse. The New York Times of February 28, 1859 described the tragic scene:

On coming up Sickles walked directly to Key, and said, “You have dishonored my bed and family, you scoundrel – prepare to die!” – at the same time drawing his pistol. Almost simultaneously Key placed his hand inside his vest, and drawing what appeared to be a pistol, but was really an opera glass, said, “You had better not shoot.”

Sickles at once fired, Key at the same time throwing his glass at him. This shot only grazed Key, slightly raising the skin of his side, and he immediately leaped behind a tree to avoid another shot. Sickles followed, and Key, catching his arm, endeavored to prevent him from firing, but Sickles disengaged himself, and firing again, shot Key in the upper part of the right thigh, close to the main artery.

Falling on his hip and supporting himself with his hand, he cried, “Murder! Don’t shoot!” Sickles still following, fired again, with his pistol close to Key, the ball passing through his body below the breast.

In the meantime the report of the pistol and Key’s cries startled those in the neighborhood. Mr. Thomas Martin, a Clerk in the Treasury Department, who happened at the moment to be leaving the Club, rushed back, and calling out, “Key is murdered!” Mr. Doyle, Mr. Upshur and Mr. Tidball, who were in the Club at the time, proceeded hastily to the spot, when they found Sickles standing over the body of Key, with his pistol presented at his head, and which he tried twice to discharge, but which snapped both times….

Charged with murder, Sickles was held without bail until his trial on April 4, 1859. Edwin M. Stanton, future Secretary of War under Abraham Lincoln, would serve as one of his defense attorneys. Since Sickles had already confessed to the killing, his attorneys decided on a novel defense – not guilty by reason of temporary insanity: “We mean to say not that Mr. Sickles labored under insanity in consequence of an established mental permanent disease, but that the condition of his mind at the time of the commission of the act in question as such would leave him legally unaccountable, as much so as if the state of his mind had been produced by a mental disease.”

After three weeks of a well-publicized trial, the case went to jury on April 26. They deliberated for 70 minutes before returning a verdict: not guilty. Dan Sickles was set free, the first defendant in American history to be acquitted of murder by reason of temporary insanity.

Two years later, at the outbreak of the Civil War, Sickles was appointed a brigadier general in the Union army. Later promoted to major general, he was in command of the III Corps of the Army of the Potomac during the battle of Gettysburg, where he was severely wounded by a cannonball and had his right leg amputated just above the knee. Sickles retired from the army in 1869, and served as the U.S. minister to Spain from 1869 to 1874. In 1893, the citizens of New York re-elected him to Congress for two years. He suffered a stroke in April 1914 and passed away two weeks later on May 3 at the age of 94.

SO… where was the “Gun Control” laws in 1859 ?