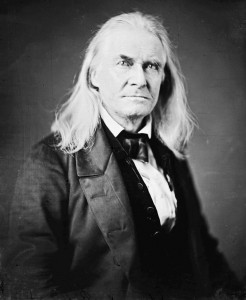

Library of Congress

The renowned Southern nationalist, Edmund Ruffin, was 67-years-old when he travelled to South Carolina and fired a cannon during the opening attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861. He was also present at the battles of First Manassas and Seven Pines before poor health confined him to home for the remainder of the Civil War. Unrepentant to the end, Ruffin had such “unmitigated hated to Yankee rule” that he committed suicide at the war’s end to keep from living in the “now ruined, subjugated, & enslaved Southern States!”

Born on January 5, 1794 in Prince George County, Virginia, Edmund Ruffin attended the College of William and Mary and served as a private in the Virginia militia during the War of 1812. After inheriting his family’s plantation after the death of his father in 1810, Ruffin became a self-taught agriculturist who developed successful methods to correct soil depletion from tobacco farming. He published his techniques in an 1832 book titled An Essay on Calcareous Manures and launched his own agricultural journal, The Farmer’s Register, in 1833.

Becoming immersed in the political events of the antebellum South, Ruffin was elected to one term in the Senate of Virginia in 1823 and became a radical supporter of slavery, states’ rights, and secession. He expressed his views in the 1850s through several published essays: The Influence of Slavery; or, Its Absence, on Manners, Morals, and Intellect; The Political Economy of Slavery; and Slavery and Free Labor Described and Compared. In 1856, Ruffin also began keeping a personal journal.

Incensed by John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, Ruffin travelled to Charles Town, (West) Virginia, to witness the hanging of the “atrocious criminal.” Disappointed to find that viewing of the event was limited to the military guard, Ruffin asked – and was granted – permission to become a recruit in the group of Virginia Military Institute cadets who were present. After the hanging, he obtained fifteen of the long metal pikes Brown had procured to arm slaves in his uprising. Ruffin sent a pike to each governor of a Southern state with a note describing it as designed “to be imbrued in the blood of the whites of the South.”

Traveling to South Carolina in 1860 to help stir the fires of secession, Ruffin eventually made his way to Charleston in the spring of 1861. There he joined Captain George B. Cuthbert’s unit of Palmetto Guards as they occupied Cummings Point on Morris Island prior to the attack on Fort Sumter. Shortly after a signal shot exploded over the fort early in the morning of April 12, 1861, Ruffin pulled the lanyard of a 64-pound Columbiad cannon, sending a shot that plunged into Sumter’s northeast parapet.

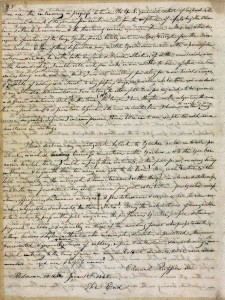

Library of Congress

Although often accredited with having fired the first shot on Fort Sumter, Ruffin fired only after the initial signal shot, writing in his journal: “At 4:30, a signal shell was thrown from a mortar battery on Fort Johnson, which had been before ordered to be taken as the command for immediate attack – & the firing from all batteries bearing on Fort Sumter next began in the order arranged….”

Ruffin’s shot apparently hit its mark, with Abner Doubleday writing in his 1876 book Reminiscences of Forts Sumter and Moultrie in 1860-’61 that “almost immediately” after the signal shot “a ball from Cummings Point lodged in the magazine wall, and by the sound seemed to bury itself in the masonry about a foot from my head, in very unpleasant proximity to my right ear. This is the one that probably came with Mr. Ruffin’s compliments.”

Following Sumter, Ruffin accompanied the Palmetto Guards to Manassas and the Peninsula early in the war, but declining health compelled him to stay in the Richmond area for the remainder of the conflict. His hatred of the North and desires for vengeance, however, only intensified after Union soldiers destroyed his homes in the Tidewater area along with his treasured library and prized collection of fossil shells.

Becoming despondent after the fall of Richmond in April 1865 and praying each night “that I may not live another day,” Ruffin decided that suicide was his only recourse. On the morning of June 17, 1865, after having breakfast with his family, he returned to his upstairs room to make his last journal entry.

Finishing his writing at 10:00 a.m., Ruffin signed and dated his diary, completing it with the notation: “The End.” But before he could carry out his final plans, he was interrupted by neighbors paying an unexpected visit. After they left at 12:15 p.m., Ruffin returned to his room, made a postscript entry to his diary, sat in a chair, and placed the barrel of a loaded rifle in his mouth. Then, with the aid of a forked stick, he pulled the trigger. The percussion cap exploded but failed to fire the rifle. After calmly replacing the cap, he pulled the trigger again, this time ending his life. Rushing upstairs upon hearing the noise, his son found Ruffin’s lifeless body still sitting in the chair with his journal on the desk open to its final entry:

And now, with my latest writing & utterance, & with what will (be) near to my latest breath, I hereby repeat & would willingly proclaim my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule – to all political, social, & business connection with Yankees, & to the perfidious, malignant, & vile Yankee race.

Suggested Reading:

Mitchell BL. Edmund Ruffin: A Biography. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1981.

Leave a Reply