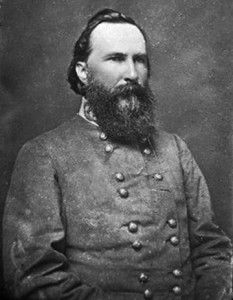

Following a successful flank attack at the Battle of the Wilderness on May 6, 1864, Lieut. Gen. James Longstreet was riding forward along the Plank Road when a volley of fire emerged from the woods to his right. Longstreet felt the sudden pain of a bullet passing through his neck and shoulder as he became yet another victim of friendly fire. The severity of the wound became quickly evident, as he recalled in his memoirs: “…[I]n a minute the flow of blood admonished me that my work for the day was done.”

The events associated General Longstreet’s injury were eerily similar to those surrounding Stonewall Jackson’s wounding, which occurred roughly four miles to the east, one year and four days earlier. And although much has been written in the past 150 years about the events surrounding Jackson’s wounding and its implications, the details of Longstreet’s wounding have, for the most part, gone largely unnoticed. However, in another similarity to the Jackson event, the actual specifics of Longstreet’s injury may be in contrast to commonly held impressions.

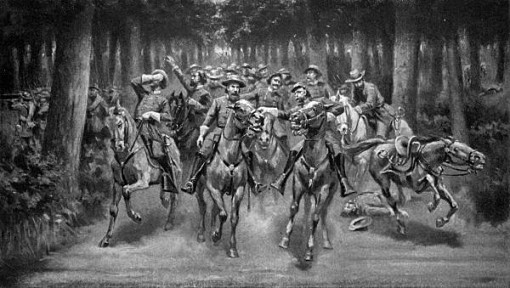

At the time of his injury, Longstreet and his staff had unknowingly ridden between separated elements of Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s brigade. The 12th Virginia Regiment had mistakenly advanced across the Plank Road, to the north side, while the rest of the brigade remained to the south. Realizing they were alone, the regiment attempted to recross the road, but just as they crested a rise north of the Plank Road, they were mistaken for Union soldiers and fired upon by the regiments to the south.

Caught in the cross-fire, Longstreet was struck by a bullet that passed through his right shoulder and neck. He attempted to continue riding forward, but the rapid loss of blood caused him to become unsteady in the saddle. Removing the general from his horse, Longstreet’s staff sat him on the ground beneath a tree. Bleeding profusely and blowing “bloody foam” from his mouth, Longstreet gave directions for his staff to have Maj. Gen. Charles Field assume command and continue the attack.

From Manassas to Appomattox

The corps medical director, Dr. John Syng Dorsey Cullen, quickly arrived on the scene, and with the general being “almost choked with blood,” managed to stem the hemorrhage from the wound. Longstreet was placed on a litter and removed by ambulance to a field hospital at Parker’s Store, where Cullen and three additional surgeons closely examined the wound, concluding it “was not necessarily fatal.”

After a period of recuperation, Longstreet would eventually return to the Army of Northern Virginia in October 1864, albeit with lingering physical impairments. “His right arm was quite paralyzed and useless….Following the advice of his doctor, he was forever pulling at the disabled arm to bring back its life and action,” wrote his chief-of-staff, Lieut. Col. Moxley Sorrel, in Recollections of a Confederate Staff Officer. Longstreet never did regain full use of his right arm and his voice remained whispery for the remainder of his life.

Historically, the bullet that struck Longstreet is believed to have entered through the front of his neck and exited through his back, near the right shoulder blade. Longstreet’s own memoirs, published in 1896, imply as much: “At the moment that Jenkins fell I received a severe shock from a minie ball passing through my throat and right shoulder.” A further examination of the event, however, reveals evidence that the ball may have actually taken the opposite path, entering the shoulder and exiting the neck.

Initial newspaper reports of the incident relate Longstreet as being wounded “in the shoulder” without any mention of a neck wound. More specifically, a May 10, 1864 article in the Richmond Daily Dispatch reports:“Longstreet was wounded painfully, but not dangerously, in the left shoulder, the ball entering obliquely and passing upwards.” Although this article places the injury on the wrong side, it implies, along with others, that Longstreet’s wound was initially thought to be shoulder-related.

On May 19, 1864, the Daily Dispatch published a second report, this time describing a wound in the opposite direction: “Longstreet was shot in the neck. The ball struck him in front on the right of the larynx passing under the skin, carrying away a part of the spine of the scapula, and coming out behind the right shoulder.” This article, apparently based on information obtained from Dr. Cullen, goes on to relate the injury as being “severe, but is not considered mortal,” and that Longstreet “has lost the temporary use of his right arm, what surgeons call the conical plexus of nerves being injured.”

For a single bullet to injure both Longstreet’s larynx and the nerves in his shoulder controlling use of the arm, it would need to take a slightly oblique path through the body, with either an upward or downward trajectory. For a downward trajectory to occur – from neck to back of shoulder – the shot would either have to come from above Longstreet or the general would have to be leaning far forward in the saddle, two unlikely scenarios based on eyewitness accounts.

Maj. John C. Haskell, one of Longstreet’s artillerymen with him at the time, stated in his own memoirs that units south of the Plank Road “fortunately…fired high” – most likely because they were aiming at the 12th Virginia, who had crested the rise north of the road. If so, that would place their volley in an upward trajectory, consistent with the bullet entering the lower shoulder and exiting higher in the neck.

Further support for an upward bullet trajectory lies in reports of the moment of impact. In his memoirs, Longstreet states that when hit, “The blow lifted me from the saddle, and my right arm dropped to my side.” Sorrel, who was also near the general, likewise writes: “The Lieutenant-General was struck. He was a heavy man, with a very firm seat in the saddle, but he was actually lifted straight up and came down hard.” Logic and physics suggest only an upward force could generate the energy necessary to lift a man out of the saddle.

Although establishing the exact mechanism of Gen. James Longstreet’s wound has little overall historical importance, it’s another example of the uncertainty one often encounters when attempting to determine the facts surrounding a significant Civil War event.

Suggested reading:

Steckler, Robert M., and Jon D. Blachley. “The Cervical Wound of General James Longstreet.” Archives of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery 126 (2000): 353-359.

Longstreet, James. From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1896.

Famous incidents like this should serve as a reminder that bullets following strange paths into and out of the body are not really so strange after all.