Following the end of Civil War hostilities in 1865, there were many in the North who wanted the civil and military officials of the Confederacy to stand trial for treason. The assassination of Abraham Lincoln further flamed the desire of many to take vengeance upon the South and its leaders, particularly Gen. Robert E. Lee.

The New York Times was a leading proponent for treason charges against Lee, writing in a June 4, 1865 editorial: “He has ‘levied war against the United States’ more strenuously than any other man in the land, and thereby has been specially guilty of the crime of treason, as defined in the Constitution of the United States,” and “whether Gen. Lee should be hung or not, is a minor question.”

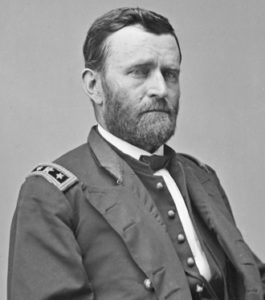

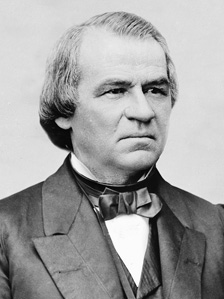

President Andrew Johnson was another advocate of harsh treatment for Lee and his generals, but he was soon to learn his views were in direct contrast to those of the North’s war hero, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. The Appomattox terms of surrender offered and signed by Grant included the clause “…each officer and man will be allowed to return to his home, not to be disturbed by United States Authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.” Grant had wanted peace and included this line to ensure there would be no future reprisals against the Confederates.

But on June 7, 1865, U.S. District Judge John C. Underwood in Norfolk, Virginia, handed down treason indictments against Lee, James Longstreet, Jubal Early, and others stating the terms of parole agreed upon with Lee were “a mere military arrangement, and can have no influence upon civil rights or the status of the persons interested.” When Lee, who was preparing to apply for amnesty, became aware of the indictments, he wrote Grant asking if the Appomattox terms were still in effect.

After reading Lee’s letter, Grant forwarded his own views to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton on June 16, 1865:

In my opinion the officers and men paroled at Appomattox Court-House, and since, upon the same terms given to Lee, cannot be tried for treason so long as they observe the terms of their parole. This is my understanding. Good faith, as well as true policy, dictates that we should observe the conditions of that convention. Bad faith on the part of the Government, or a construction of that convention subjecting the officers to trial for treason, would produce a feeling of insecurity in the minds of all the paroled officers and men. If so disposed they might even regard such an infraction of terms by the Government as an entire release from all obligations on their part. I will state further that the terms granted by me met with the hearty approval of the President at the time, and of the country generally. The action of Judge Underwood, in Norfolk, has already had an injurious effect, and I would ask that he be ordered to quash all indictments found against paroled prisoners of war, and to desist from further prosecution of them.

Grant also visited personally with President Johnson to discuss the situation, but was dismayed to find that Johnson fully intended to let the proceedings continue. Grant insisted the Appomattox terms be honored. Johnson asked when the men could be tried. “Never,” Grant responded, “unless they violate their paroles.”

Andrew Johnson, however, was just as stubborn as Grant and told the general he wouldn’t interfere with the prosecution. Grant too refused to back down, telling the President he would resign his commission if the surrender terms were not honored. Johnson realized he had lost; the public would never support him over the far-more popular Grant. Word was sent to the U.S. District Attorney in Norfolk to drop the proceedings.

Grant then responded to Lee’s letter. Copying his comments to Stanton in the reply, he wrote on June 20, 1865: “This opinion, I am informed, is substantially the same as that entertained by the Government.” Lee was safe from trial, but Grant never told him how far he had gone to protect him.

Suggested reading:

Badeau, Adam. Grant in Peace. From Appomattox to Mount McGregor. Hartford, CT: S.S. Scranton & Company, 1887.

Simon, John Y., ed. The Papers of U.S. Grant. Vol. 15. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1988.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, DC, 1880-1901), Series 1, vol. 46, pt. 3, 1275, 1287.