Over the years, a previous article on Civil War Nicknames has remained one of the most popular posts on this site, so much so that a sequel to the original seems to be in order. As soldiers and the public seemed to relish bestowing leaders with such monikers, the following discussion is still by no means an exhaustive list of nicknames – even for a single individual in some cases.

Battlefield performance, good and bad, was a frequent basis for many nicknames. Seeming to appear and disappear from thin air, “Mosby’s Rangers” were so elusive that Confederate cavalryman John Singleton Mosby was famously referred to as “The Gray Ghost.” William T. Anderson’s barbaric and brutal guerilla tactics in Missouri were the source for his “Bloody Bill” nickname.

Union general Winfield Scott Hancock became “Hancock the Superb” after a Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan telegram informing Washington that “Hancock was superb today” during the Peninsula Campaign of 1862. McClellan’s own procrastinating and plodding in orchestrating the same campaign, however, led him to be called “The Virginia Creeper.”

“Stonewall” Jackson captured so many supplies from Nathaniel P. Banks’ Union army during the Shenandoah Valley Campaign that Confederate soldiers began referring to the general as “Commissary Banks.” A supposed newspaper typographical error resulted in Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker being titled “Fighting Joe,” a nickname Hooker actually disliked and one that caused Robert E. Lee to wryly refer to him as “Mr. F.J. Hooker.”

Childhood nicknames that continued into the war include William Tecumseh “Cump” Sherman and James “Pete” Longstreet. Robert E. Lee’s son, William Henry Fitzhugh Lee, was known as “Rooney” to differentiate him from his contemporary cousin, Fitzhugh or “Fitz” Lee.

Union general Benjamin Butler received two nicknames during his tumultuous 1862 stint as military governor of New Orleans. He was “Spoons” Butler after his alleged participation in seizing a citizen’s silverware as wartime contraband and became “Beast Butler” after issuing a general order stating any female who insulted a Union soldier by word or deed would be legally regarded a prostitute.

The aged Gen. Winfield Scott was known as “Old Fuss and Feathers” for his love of discipline and pomp, while Henry W. Halleck became “Old Brains” because of his expertise and publications on military science. Maj. Gen. George Meade had a notorious short-temper and facial features that caused many to refer to him as “a damned old goggle-eyed snapping turtle” or “Old Snapping Turtle” for short.

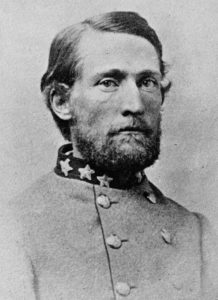

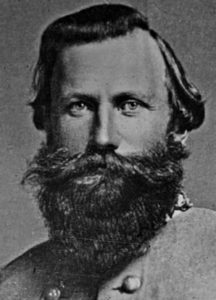

Due to his habit of blinking excessively when talking, Union general William H. French was called “Old Blinky.” Confederate cavalry general J.E.B Stuart (whose initials made him known as “Jeb”) was sarcastically known as “Beauty” during his West Point days because his weak chin resulted in a more homely appearance. The growth of his long beard eventually hid the facial feature, leading one fellow officer to remark that Stuart was “the only man he ever saw that (a) beard improved.”

And finally, Union Maj. Gen. Edwin Vose Sumner was known as “Bull Head” (at times shortened to “Bull”) since the Mexican-American War where, during the Battle of Cerro Gordo, a spent musket ball bounced off his head.

What a fun post! Virginia Creeper? Turtle Meade? I’m afraid I’ll never be able to look at some of these characters the same way again.