Library of Congress

I recently had the pleasure of attending a superb lecture by author and fellow blogger Eric Wittenberg on the Battle of White Sulphur Springs. At the conclusion of the talk, he mentioned that Brig. Gen. William W. Averell, who commanded Union forces during the battle, had made a small fortune after the war by patenting a new formula for asphalt. His comment prompted me to delve further into the story.

William Woods Averell was born in Cameron, New York, on November 5, 1832. After graduating from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1855, he was commissioned a lieutenant in the U.S. Cavalry. Following the Battle of First Manassas in 1861, he was appointed colonel of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry. He rose to the rank of brigadier general of volunteers in 1862 and was placed in command of a cavalry brigade assigned to the Army of the Potomac. When Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker later reorganized the army, Averell was placed in command of the Second Cavalry Division.

Although he would receive accolades for “gallant and meritorious service” during the Battle of Kelly’s Ford in March 1863, Averell’s fortunes as a military commander would soon dwindle.

Becoming one of Hooker’s scapegoats for his defeat at Chancellorsville, Averell was relieved of command and sent to Wheeling, WV, to assume control of the Fourth Separate Brigade. Although his forces were repulsed at the Battle of White Sulphur Springs, WV, in August 1863, Averell subsequently led his men to victory at the Battle of Droop Mountain in November 1863. He followed that with a successful raid against the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad in December of the same year.

When Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan took command of the Army of the Shenandoah in 1864, Averell was appointed to command a division of cavalry. His prudence as a commander, however, caused him to fall into disfavor with Sheridan too, who dismissed Averell from command after the Battle of Fisher’s Hill. Sent back to West Virginia, Averell would never again command troops in the field.

Following the war, Averell became an entrepreneur. He first tried the oil business, establishing the Averell Coal and Oil Company in June 1865. After that firm experienced serious operational troubles, he briefly tried his hand in steel making. His interests then changed to asphalt after seeing it used experimentally to pave several streets in New York City and Newark, New Jersey. Although there were problems with the early asphalt, Averell was convinced of its potential as a road surface if the right formula and methods for laying it could be developed. He became president of the Grahamite Asphalt Pavement Company in 1870 and began a series of experiments to improve both the material and the techniques used to apply it.

Due to conflicts with his business partner, Averell reorganized the Grahamite Asphalt Pavement Company into the Grahamite and Trinidad Asphalt Company in 1873, and a year later the firm was again reorganized and renamed the New York and Trinidad Asphalt Company. The business then became the recipient of two major and high profile contracts in 1875. The first was to repave Fifth Avenue in New York City, and the second was to pave Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. In 1876, the company successfully paved the famous D.C. thoroughfare from 6th Street up to 15th Street, near the White House.

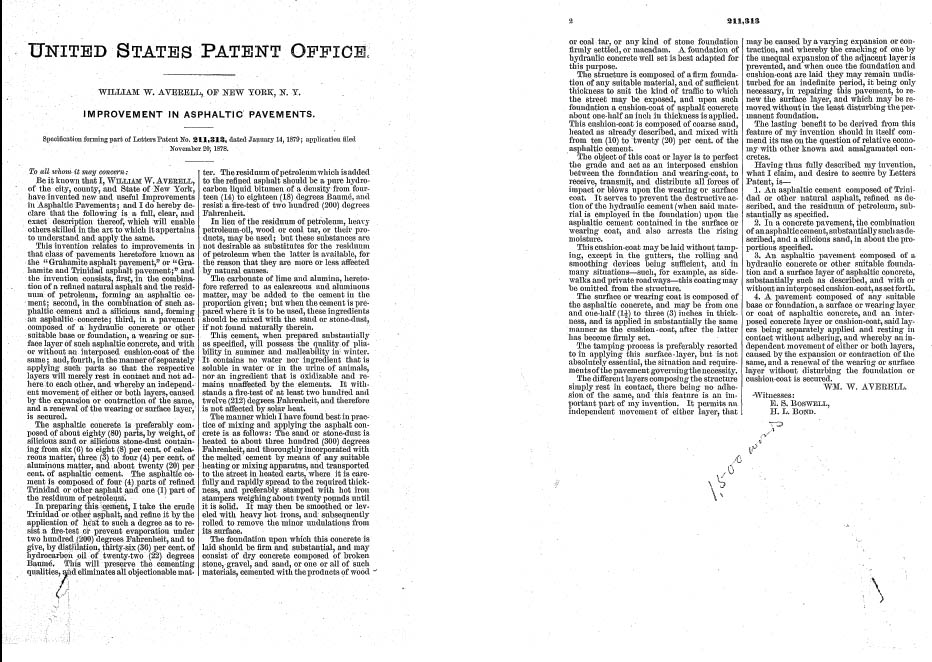

On January 14, 1879, William Averell was awarded a U.S. patent for “Improvement in Asphaltic Pavements,” which included both a new formula for asphalt and the technique for laying it. In 1884 and 1886, he would receive additional patents for an asphaltic conduit for underground electrical systems, such as those intended to propel streetcars. His dealings with multiple business partners and companies in the asphalt business eventually resulted in a number of court battles over royalties and infringement of patent rights. After years of trials and delays, the legal wrangling finally ended in 1898 when he won a $700,000 award against a rival company.

Seeking to obtain some degree of restitution for his perceived mistreatment at the hands of his former military commanders, Averell was briefly reinstated into the U.S. Army by a Special Act of Congress in August 1888 in recognition of his “long and faithful services…before and during the late war.” This was followed by an appointment from President Grover Cleveland to the position of Assistant Inspector General of Soldiers’ Homes. In his new post, Averell travelled among hospitals evaluating their conditions for the care and treatment of veterans. He resigned the position in 1898 and died two years later in Bath, New York, on February 3, 1900 at the age of 67.

The William Woods Averell Papers, 1836-1910 are housed in the New York State Library.

The lecture to which Dr. Lively refers was a part of a series of lectures presented at the West Virginia Mason-Dixon Civil War Roundtable’s annual Symposium held at Erickson Alumni Center at West Virginia University on April 6, 2013. The Symposium was funded by the West Virginia Commission for the Sequicentennial of the American Civil War and co-sponsored by the Department of History at WVU and the Stonewall Jackson CWR of Clarksburg, WV. Dr. Lively is a member of the WVMDCWR and has contributed many lectures to our organization as well as others on Civil War Medicine. Thank you, Matt for following up on this very interesting topic regarding Averill’s post-war career.

You’re welcome. It was a well-done and informative symposium. I’m already looking forward to next year.

General Averell was my 3x Great Uncle. The story of his Asphalt business can be followed by exploring his personal papers in Albany. He did indeed create through years of experiments the process of using the mercurial substance of asphalt as quality pavement but he allowed a real estate tycoon into his business and while the General was ill, Mr. A, Barber ruined his promising business and used his successful methods to become the Asphalt King. Averell sued him for 13 years and was near broke in the process. This is why he was eager to get the Inspector job. Yes -He finally won the law suit but he died two years later. Today, Averell’s achievement and contribution to asphalt paving is hardly recognized. One reason is because Barber wrote the history and never mentioned Averell who persistently sued him for over a decade. It is an interesting story yet to be told.