Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

In the summer of 1864, Dr. Luke P. Blackburn, a Kentucky-born physician turned Confederate agent, allegedly instituted a bioterrorism plot against United States cities and President Abraham Lincoln. Blackburn’s goal was to “release” Yellow Fever through the distribution of infected clothing, with specific articles being sent directly to Lincoln. The plot was unsuccessful, however, mainly due to a 19th century misunderstanding of how Yellow Fever is transmitted, but also because a disgruntled fellow conspirator revealed the plot to U.S. authorities.

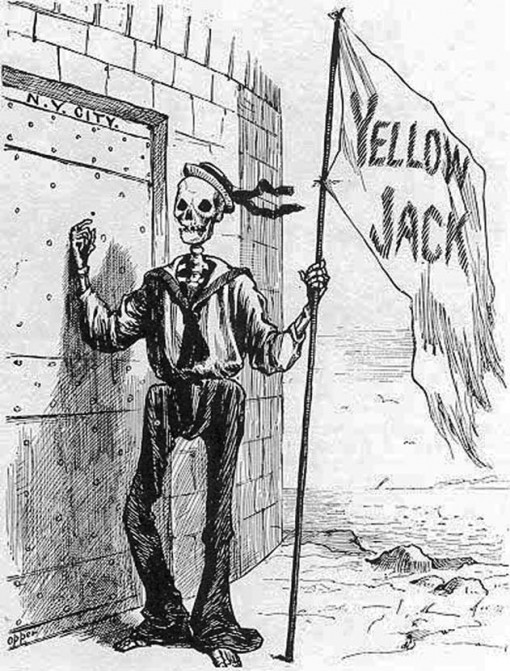

Yellow Fever, also known as “Yellow Jack,” after the flag that was flown from quarantined ships in harbors, was a deadly disease in U.S. coastal cities during the 1800’s (an 1853 outbreak in New Orleans, Louisiana, produced 9,000 deaths – 28% of the city’s population). The disease was notorious for causing “black vomit,” an ominous clinical sign resulting from hemorrhage in the stomach.

Today we know that Yellow Fever is a virus that is spread through the bite of infected mosquitoes. But during the Civil War, which occurred prior to the discovery of germs being the source of disease, medical science and the lay population believed Yellow Fever could be contracted from direct exposure to those who were infected, primarily through contact with “black vomit.” It was this belief that led Blackburn to “contaminate” clothing for distribution.

The island of Bermuda was a major base of blockade running for the Confederacy and when a Yellow Fever epidemic occurred there in the summer of 1864, Dr. Blackburn, who had extensive experience treating the disease in the Deep South, traveled from Canada to Bermuda to lend his expertise in controlling the outbreak. While on the island, Blackburn took the soiled bedding and clothing of infected patients and packed them into trunks with new shirts and coats in an effort to “infect” the unused garments with Yellow Fever particles.

Blackburn then traveled to Halifax, Nova Scotia, in June 1864 with five trunks and one valise of infected clothing. Once there, he offered a man named Godfey Hyams the sum of $100,000 to smuggle the trunks into “Washington City, to Norfolk, and as far South” as he could go “where the Federal Government held possession and had the most troops.” He instructed Hyams to dispose of the new clothing by auction with the exception of the valise, which was to be delivered by express to President Lincoln as a gift. Blackburn also specified the contents of the largest trunk were to be sold in Washington, D.C., callously remarking: “It will kill them at sixty yards.”

Hyams agreed to smuggle the trunks into the United States and points farther south, but later testified that he refused to take possession of the valise destined for Lincoln. In July 1864, Hyams had the trunks shipped to Boston and then expressed to Philadelphia. Traveling under the alias of J.W. Harris, Hyams took possession of the trunks in Philadelphia en route to Washington, D.C. Once in the capital city, Hyams turned over a portion of the clothes to a merchant who sold them at auction the following day. The remainder of the clothing he gave to a sutler traveling to Newbern, North Carolina, then controlled by the Union army, with an agreement to sell it on commission. His task complete, Hyams returned to Canada for payment.

Blackburn and Hyams met again in Canada, but the physician refused to pay Hyams the promised sum pending proof he had disposed of the clothing as directed. While Hyams wrote to and awaited a receipt from the Washington merchant, Blackburn went back to Bermuda to aid in yet another Yellow Fever outbreak.

During his second visit to Bermuda, Blackburn repeated his process for infecting garments and contracted the services of a man named Edward C. Swan to hold three trunks of contaminated clothing until the following spring when he was to ship them to New York City for “the destruction of the masses there.” The plot would unravel, however, before the trunks ever left the island.

In April 1865, a now frustrated and unpaid Godfrey Hyams walked into the United States counsel’s office in Toronto offering to expose Confederate espionage operations in Canada in exchange for money and immunity. Two days later, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in Washington, D.C.

During the subsequent Lincoln Assassination Trials, Hyams was brought to Washington as a government witness to Confederate plots against the president. When asked during trial if Dr. Blackburn had informed him of being successful in sending the valise to Lincoln, Hyams replied: “No sir, but I have heard it was sent to him.” No record exists as to what actually became of the valise or the clothes specified for Lincoln.

As the events unfolded in Washington, Blackburn’s second plot in Bermuda was exposed after an informant tipped the island’s U.S. counsel’s office that trunks of infected clothing were located at the house of Edward Swan. Bermuda police and heath officers confiscated the trunks and arrested Swan for “harboring a nuisance, detrimental to the health of the community.”

National Library of Medicine

During Swan’s Bermuda trial, the health officer testified to finding trunks of new clothes packed with clothing, sheets, and pillow cases stained with “black vomit.” Nurses also testified they witnessed Blackburn taking soiled linen from patients and packing them into trunks that he removed from the houses.

Armed with testimony from the Lincoln Assassination and the Edward Swan trials, U.S. officials urged Canadian authorities to apprehend Luke Blackburn, who was now back in Montreal. On May 19, 1865, Blackburn was arrested, charged with conspiracy to commit murder, and transferred to Toronto to stand trial. His charges were later reduced to a violation of Canada’s neutrality since, under then current British law, conspiracy to commit murder could only be charged if the intended victim was a head of state. Lacking sufficient evidence that Blackburn’s target was such an individual, the physician instead stood trial on the neutrality charge.

Blackburn was acquitted of all charges on the basis that no evidence existed the trunks had ever been on Canadian soil, thus violating its neutrality. Back in the United States, as the Lincoln Assassination Trial shifted focus to John Wilkes Booth and his conspirators, officials there also lost interest in Blackburn and never sought his extradition from Canada.

Luke Blackburn remained in Canada until late 1867 when he traveled to New Orleans to assist with a Yellow Fever epidemic that would ultimately result in more than 3,000 deaths in the city. He would eventually make his way back to his native state of Kentucky, moving to Louisville in 1873, where he reentered private practice as a physician.

In 1878, Blackburn entered politics by running for Governor of Kentucky. Remaining silent when newspapers questioned his alleged involvement in the Yellow Fever Plot, Blackburn commented only once in 1879 that the accusations were “too preposterous for intelligent gentlemen to believe.” Winning the 1879 election by a wide margin, Blackburn served one-term as governor before eventually succumbing to health problems and passing away at the age of 71 in 1887.

Suggested Reading:

“The Yellow Fever Plot.” Medical and Surgical Reporter, 1865; 12(35): 565-567.

Records Relating to Lincoln Assassination Suspects Entered in the Register of the Military Commission. http://www.footnote.com/documents/6390467/lincoln-assassination-papers.

Baird ND. Luke Pryor Blackburn: Physician, Governor, Reformer. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1979.

What happened in N. C.? Was the sutler going to New Bern arrested or caught. We had some bad diseased outbreaks in Wilmington during the war and perhaps

other places.

Cordially,

John R.

We have no details of what became of the sutler or the clothes. He was apparently an unknowing participant in the plot, much like the Washington, DC merchant who sold the clothes at auction. An outbreak of Yellow Fever did occur in New Bern during the fall of 1864 that resulted in the death of nearly 300 hundred Union soldiers; but since the disease can only be transmitted by mosquitoes, it was merely a coincidence. At the time, however, it did reinforce the idea to the conspirators that the plot was working.